Revisiting the Impacts of the Green Revolution in India

Introduction

It was 1947. India had gained its freedom from British rule, but like many countries worldwide in the aftermath of World War II, the new nation was experiencing severe food shortages. The war-induced famine in Bengal in 1943 had earlier resulted in the death of between 1.5 and 3 million people. In 1947, the country’s food supply was again disrupted as the agrarian state of Punjab in northwestern India was divided by the agreement creating the new state of Pakistan. This territorial division also left Punjab without any of its primary agricultural research facilities, as the Agricultural College and Research Institute at Lyallpur, Punjab, was now located in Pakistan. To help to fill the supply gap it now confronted, India relied on food imports from the United States.

In fact, throughout much of the Cold War era, then Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi (1966-1984) “hoped” for USA food aid without openly admitting to doing so. India faced two severe droughts in 1964-65 and 1965-66, leading to shortages of food once more. Those events resulted in India receiving 5 million tons of wheat aid from the U.S. Food for Aid Program. Overall, India received American aid in the form of concessional food sales totaling 10 billion dollars between 1950-1971 to purchase 50 million tons of emergency food from the United States. The government of India expected to have to import an estimated 10 million tons of cereal grains per year by the 1980s to feed its growing population and it did not then have an overarching plan to address the issue.

However, the story was different in the small northwestern Indian state of Punjab. The name Punjab is derived etymologically from the Persian words panj (five) and āb (waters), meaning "the land of five rivers." Punjab occupied about 2% of India's land area following the 1947 partition that created Pakistan. After rebuilding its economy following its division, Punjab emerged as one of the wealthiest states in India. Blessed with natural surface water resources, as its name suggests, and having been willing to undertake fundamental institutional and land reforms after independence, the state’s government also worked to develop irrigation systems, electric power resources, a foundation of agricultural research and extension and a solid cooperative credit structure for its population. During a period when India overall was struggling to meet the food needs of its citizenry, the state of Punjab recorded a 4.6% growth rate in agricultural production between 1950-1964 (before the Green Revolution) and became more than self-reliant in fulfilling the needs of its population as a result (Bhalla et al., 1990). The nation farmers were ready to assist when the opportunity presented itself do so in the form of the Green Revolution.

The Green Revolution Era

In April of 1969, 16 leaders from the world's major foreign assistance agencies and eight scientific food production consultants met at the conference center at Villa Serbelloni, Italy to devise a strategy to feed the world's hungry through science, rather than food aid (Hardin 2008). The government of India selected Punjab to receive a Green Revolution support "package" recommended by the conference because of the state’s track record of working effectively to improve its agricultural production. One example of that innovation had occurred in the mid-1960s before the Green Revolution. India imported 18,000 tons of dwarf wheat seeds from Mexico in 1966. Punjab seized the initiative in transporting its share of that shipment from their port of arrival via trucks to ensure timely arrival, while other states awaited trains for transport. Meanwhile, the state’s Corrections Department arranged for prisoners to prepare an adequate number of 10kg bags to distribute the new seeds to farmers when they arrived in Punjab. This effort, in concert with the state’s previous initiatives to ensure adequate support of its growers, persuaded the Indian central government that Punjab possessed the political, social and economic wherewithal to accept and make productive use of Green Revolution technology.

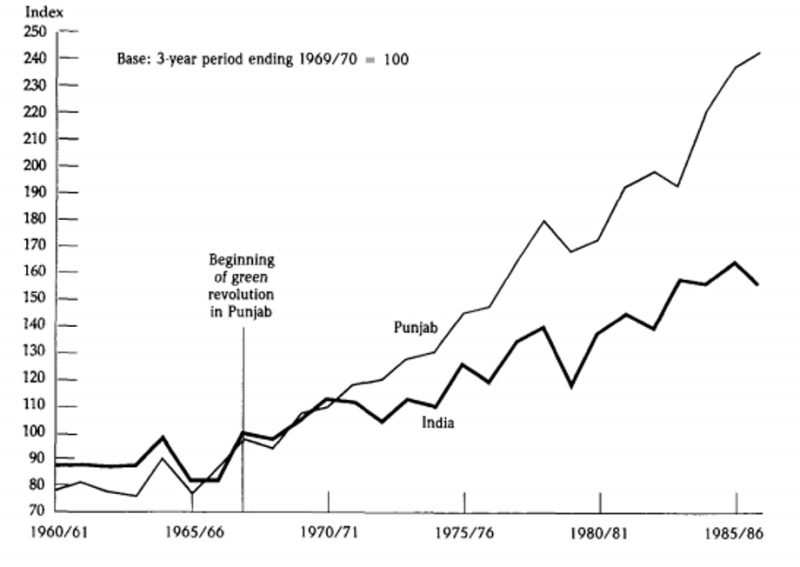

And so began the tale of India's journey toward agricultural self-reliance. The early years of the Green Revolution required that Punjab’s farmers replace indigenous seeds with new high yielding varieties (HYV). Those varietals absorbed higher levels of nitrogen than their native counterparts and required synthetic fertilizers as a result. Punjabi farmers also began to employ pesticides in their fields to boost yields. Farmers likewise replaced traditional diverse crop choice strategies with wheat and rice monocropping. These steps resulted in a phenomenal rise in wheat and rice production in the state (Figure 1). Wheat yields increased by 2% per year from 1952-65 and rose again annually by an average of 2.6% during the 1968-85 period. Meanwhile, Punjab’s rice production increased from typical growth rates of 1.7% per year in the pre-Green Revolution era to 5.7% annually from 1967 to 1985. Rice cultivation had traditionally been low in Punjab; the state produced 0.1 million metric tons in 1950 and 0.5 metric million tons in 1970, for example. But with the introduction of Green Revolution strategies, this value rose to 5.1 million tons per year by 1985 and it reached a record high of 12 million tons in 2017. Meanwhile, wheat output increased from 1 million tons in 1950 to 10.2 tons in 1985 (Bhalla et al. 1990). As a result, wheat and rice soon emerged as the two dominant crops grown in the state. The upshot of this growth in production during the 1970s was that Punjab virtually single-handedly delivered India its much-desired food independence. When the famine of 1975 struck, India was prepared to address it because its farmers were equipped with sturdy, disease-resistant, fast-growing, and highly responsive seeds to face that challenge. Indeed, India emerged as an exporter of food grains for the first time after independence during the 1970s (Figure 1).

As the Green Revolution proceeded, the net area irrigated as a percentage of total hectares in crops in Punjab increased from 49% in 1950/51 to a high of 81% in 1980/81. The net area irrigated by tube wells specifically, increased from 35% in 1950 to 57% of total planted area in 1980. By 1981, Punjab boasted one tube well for every 7 hectares of land in cultivation. Meanwhile, the state government electrified 100% of the state’s villages by 1980, compared to 47% for India’s rural communities as a whole. At the same time, the number of tractors in use by Punjabi farmers increased more than 11 times between 1966-1981.

Even before the Green Revolution, the national government had sought to ensure a favorable price environment and means to procure grain to help farmers invest in new technologies. To do so, India’s Parliament established the Food Corporation of India (FCI) in 1965. The FCI guaranteed the purchase of farmer produced grains at a minimum support price (MSP). The government sought to use the MSP to protect the country’s growers against an excessive fall in crop prices during high production years. During the 1970s, Punjab’s farmers benefitted from the fact that they produced more food than the population of their state could consume and the FCI ensured that they were adequately compensated for that production. By 1983/84, per capita income, for example, in Punjab was 3,560 rupees compared to the national average of 2,288 rupees (Bhalla et al. 1990). In short, by the early 1980s Punjab had fulfilled the goals of the founders of the Green Revolution and emerged as a champion in India’s war against hunger. Nevertheless, new challenges lay just around the corner.

More particularly, their narrow focus on "increasing production" came back to haunt Punjab’s farmers as they replaced heirloom seeds with new HYVs. The principal reason for the change was not inadequate indigenous seed yields, but their inability to withstand the application of chemical fertilizers and pesticides (Sebby 2010). Farmers replaced the native crop varieties with expensive high yield and chemical and disease tolerant varieties. The new seeds/crops replaced thousands of locally indigenous species and the agricultural systems they had sustained (Shiva 1993). In addition to adopting widespread chemical fertilizer and pesticide use, Punjab’s farmers replaced their traditional sustainable farming practices, involving diverse cropping and leaving fields fallow periodically to allow for the regeneration of nutrients, with monocropping. As the national and state governments achieved their targets for food production and security and shifted their focus to other areas, however, Punjabi farmers found themselves coping with the aftermath of these changes.

Post-Green Revolution

After an initial period of success, the switch away from indigenous agricultural practices trapped farmers in high-interest loan cycles as they sought to pay for expensive artificially developed seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. Jodhka found in a study undertaken in the 2004-2006 period that 86% of farmers in Punjab incurred short-term loans to plant crops each year and 27% had recently borrowed to purchase farm machinery (Jodhka 2006). The irrigation systems needed to keep up production also demanded new wells to keep pace. This imperative also increased farmers’ capital costs in addition to exploiting groundwater resources. Punjab's Green Revolution farmers soon found themselves addressing high and continuing costs for seed, chemicals, fertilizer and irrigation as well as rapidly depleting soils.

The ecological impacts of the adoption of modern high production agriculture in Punjab proved far reaching indeed. While some rice had always been grown in the region, it was not a native crop in the state, and farmers soon found that this incompatible climatic crop was depleting their water resources. Where once farmers could drill 10 feet and find water for irrigation, in many areas of the state today they must drill to 200 feet to do so and that depth is increasing at a rate of about 3 feet per year (Mohan 2020). In addition, Punjab alone today consumes 20% of India’s pesticides each year. The human consequences of this turn are visible in numerous areas of the state, which have experienced a marked rise in cancer cases, stillborn babies and congenital disabilities (Zwerdling 2009).

By the early 2000s the state and its farmers faced a crisis. In fact, Swaminathan, the father of the Green Revolution in India, has argued that the practices adopted as a part of that movement may not have been the best approaches for the long run sustainability of farming in the nation generally and in Punjab more particularly (Kesavan and Swaminathan 2018). Instead, as noted above, the industrialization and monoculture strategies advocated by Green Revolution enthusiasts have resulted in low water tables and depleted soils in Punjab. These techniques initiated a cycle in which farmers spent more and more on chemicals and pesticides to offset the deepening negative impacts of monoculture cropping.

Today, residents of Punjab are turning their backs on genetically modified produce and also eschewing products from other regions produced with high quantities of pesticides and fertilizers. Nonetheless, overall returns, including the government’s MSP, which only supports commodities such as wheat and rice, have made it difficult for the state’s farmers to shift away from existing high input agricultural practices. Many Punjabi growers today feel trapped between securing a living and supporting a sustainable farming system (Jodhka 2006).

In retrospect it seems clear that after Punjab’s farmers worked as requested to increase production during a period of national need, their national and state governments should have helped them modify their high intensive practices when evidence mounted that those strategies were destroying the environment and trapping them in debt. However, that never happened.

In fact, by the 2000s, the MSP was no longer increasing at the same rate as it had previously. In the first decade of the 2000s, Punjab’s farmers delivered bumper crops and the heaps of grain could be seen in farmers’ markets across the state. But the FCI now declined to buy needed quantities from those growers, citing “quality” concerns. Farmers were left with no choice but to sell their harvest at a price lower than the MSP nominally supported. This situation, which has continued, has resulted in at least 7000 suicides among farmers since 2000 in Punjab. Some observers have argued that the actual number may be three times this government-issued figure (Singh 2018).

This mounting economic and social crisis arose in major part due to a change in government priorities once the nation achieved food security. In the 1990s, Indian leaders began to emphasize the need to create a "new economy" and both the national and state governments have focused their primary energies on information technology and urban consumers since (Jodhka 2006). Nonetheless, aware of this deepening predicament, the newly elected Indian government (in 2004) formed the National Commission on Farmers (NCF) chaired by Swaminathan in November 2004 to address the causes of farmer distress in the nation. In its 5-part report, the Commission suggested a comprehensive national policy to support the nation’s farmers (Sanyal 2006). The report focused on land reforms, investments in surface water systems, adoption of groundwater recharge schemes and promotion of conservation farming to preserve soil health and water quality and quantity. The report also emphasized the need to reduce the interest rate for crop loans, initiate a comprehensive crop insurance scheme, increase the MSP by at least 50% of the weight cost of production and extend the price support program to crops other than wheat and rice. However, 16 years after its publication, vigorous debate continues concerning whether the government has taken sufficient steps to implement its provisions.

What Does the Future Hold?

The Indian government issued three new farm ordinances on June 5, 2020 (they became law on September 24, 2020) amid the COVID-19 crisis. The Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Ordinance, 2020, the Farmers Empowerment and Protection Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Ordinance, 2020 and the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020 (Singh, Rosmann and Bailey, 2020). These laws have resulted in widespread farmer protests against the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government of India. Protestors have called these ordinances a "death warrant for farmers" because together, they argue, they deprive growers of the laws and agencies that had been in place to protect them. Contrary to the 2004 Commission report’s recommendations, these ordinances loosened rules concerning contract farming and public regulation of crop pricing and sales.

Historically, farmers sold their harvest at state government regulated markets under strictures aimed at safeguarding them from large retailers' exploitation. In contrast, the new ordinances allow farmers to sell their produce outside state markets. The legislative aim of this change was to create more competition and better pricing by encouraging additional private buyers. However, protesting farmers have argued that the ordinances embraced these changes without also ensuring adequate government price supports for their harvests. Growers fear that lifting regulation in this way without assuring adequate MSP support, will ultimately allow large companies a much greater, and largely negative in pricing terms, role in local agricultural markets.

These ordinances also create a framework for contract farming in which large retailers could buy quantities of agricultural products for a pre-agreed price. However, farmers argue that they lack control and compensating knowledge when offered these contracts and that the ordinances do too little to protect their rights when disputes arise with such purchasers. That is, contract farming shifts the power balance away from the farmer to companies. Another provision of recent policy changes removed cereal, beans, oilseeds, edible oils, onions and potatoes from the national government’s list of essential commodities. In other words, the government has now indicated that it will not regulate production and storage of these commodities. Many farmers and other critics of this change are now contending that it could lead to the monopolization of supply of these commodities by a limited number of corporate growers, which could then manipulate production to maximize their returns.

It remains unclear why the national government enacted these changes despite large protests and opposition from the nation’s farmers. But part of the answer appears to lie in India’s ongoing dialogue with the World Trade Organization (WTO) concerning the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA). The AoA is based on free trade in agriculture without barriers, and WTO views state support in the form of subsidies, including the MSP specifically, as a hindrance to achieving a free market agricultural economy in India.

Conclusion

Punjab, often known as the “Granary of India,” made India self-sufficient in agricultural production, but in so doing, also lost its traditional form of agriculture and depleted its water resources and soils considerably. The distrust among farmers of the government has now risen to perhaps its highest level in the post-Green-Revolution era. Growers are in dire need of a plan focused on sustainable farming and soil and water reclamation plans and the Report of the National Commission on Farmers provided an excellent template for needed reforms. The Indian government, however, has chosen a different course in its recently passed policies. The new ordinances do not stress sustainable farming and contract farming looks likely only to increase stress on already stressed lands. As Wendell Berry has argued, “A good farmer who is dealing with the problem of soil erosion on an acre of ground has a sounder grasp of that problem and cares more about it and is probably doing more to solve it than any bureaucrat who is talking about it in general (Berry 1972). There is no doubt that existing government regulation needs an overhaul, but farmers are now insisting that power should remain with the government in any such changes and that new regulatory policies should address needed changes in farming practices. The more market-oriented approach of recent agricultural policy changes has thus far met with widespread popular outrage across India.

References

Berry, Wendell. “Think Little: Essays.” 1972. https://berrycenter.org/2017/03/26/think-little-wendell-berry/.

Bhalla, G S, G K Chadha, S P Kashyap, and R K Sharma. 1990. “Agricultural growth and structural changes in the punjab economy: an input-output analysis centre for the study of regional development at jawaharlal nehru university.”

Hardin, Lowell S. 2008. “Meetings That Changed the World: Bellagio 1969: The Green Revolution.” Nature. Nature Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1038/455470a.

Jodhka, Surinder S. 2006. “Beyond ‘Crises’: Rethinking Contemporary Punjab Agriculture.” Economic and Political Weekly. 2006.

Kesavan, P C, and M S Swaminathan. 2018. “Modern Technologies for Sustainable Food and Nutrition Security.” REVIEW ARTICLES CURRENT SCIENCE. Vol. 115. http://www.fao.org/ag/portal/age/age-news/detail/.

Mohan, Neeraj. 2020. “Breaking Wheat-Paddy Cycle a Must to Save Groundwater: CSSRI Study - Cities - Hindustan Times.” HIndustan Times. 2020. https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/breaking-wheat-paddy-cycle-a-must-to-save-groundwater-cssri-study/story-Dw2Zperrefw8WecQkrEriM.html.

Sanyal, Kaushiki. 2006. “Report Summary Swaminathan Committee on Farmers .” PRS Legislative Research. 2006. https://www.prsindia.org/sites/default/files/parliament_or_policy_pdfs/1242360972--final summary_pdf_0.pdf.

Sebby, Kathryn. 2010. “The Green Revolution of the 1960’s and Its Impact on Small The Green Revolution of the 1960’s and Its Impact on Small Farmers in India Farmers in India.” https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/envstudtheses.

Singh, KanwalRoop. 2018. “A Pattern of Farmer Suicides in Punjab: Unearthing the Green Revolution | KALW.” December 4, 2018. https://www.kalw.org/post/pattern-farmer-suicides-punjab-unearthing-green-revolution#stream/0.

Singh, Santosh K, Mark Rosmann, and Jeanne Bailey. 2020. “Government of India Issues Three Ordinances Ushering in Major Agricultural Market Reforms.”

Zwerdling, Daniel. 2009. “In Punjab , Crowding Onto The Cancer.” NPR Publications, 2009. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=103569390.

Laljeet Sangha (Lal) is a Ph.D. student in the Water Systems Lab within the Department of Biological Systems Engineering at Virginia Tech. Lal received his BS from Punjab Agricultural University and MS from Auburn University, Alabama. His current research focuses on analyzing the future water quantity challenges in Virginia. Growing up in a small village in Punjab and an agriculturally oriented environment, he developed a keen interest in agriculture at a young age. He enjoys working with farmers and one day aspires to be the bridge between policymakers and farmers. In his free time, Lal enjoys reading traditional Punjabi literature, taking walks at the Duckpond and nature photography.