Dorothy Venable named the inaugural honoree of the annual Virginia Tech Institute for Policy and Governance Award for Moral Imagination and Courage

June 10, 2025

By Steve Hemphill and Max Stephenson Jr.

When the Calfee Community and Culture Center (CCCC) project launched in 2018, its organizers sought to develop plans to repurpose the 15,000 square foot historic Calfee Training School building in a way that appropriately honored its original educational mission to serve Pulaski County’s segregation era Black community and its youngsters.

Center leaders are today seeking to ensure that this vital part of Pulaski’s history will be available to future generations in part by naming a new Digital Lab, slated to open in 2026, after Dorothy DeBerry Venable, a beloved second grade teacher at the Training School. The Lab will serve as a resource for those seeking basic computer skills, access to advanced digital editing materials or workforce development classes.

For her part, the Lab’s namesake, Dorothy Venable, who at 93 is the last living Calfee Training School teacher, admits to being uneasy about the attention her teaching career at Calfee has received as the Center has developed, "I don't want to sound like a braggart," she said. "I was just one teacher in one classroom."

Her former students, and many others who have only recently come to know her, however, believe her impact on her students was extraordinary. To honor her remarkable legacy, the CCCC has selected her as an inaugural recipient of its Calfee Center Legends of Excellence award, whose members will be featured permanently in the facility’s African American Heritage Center.

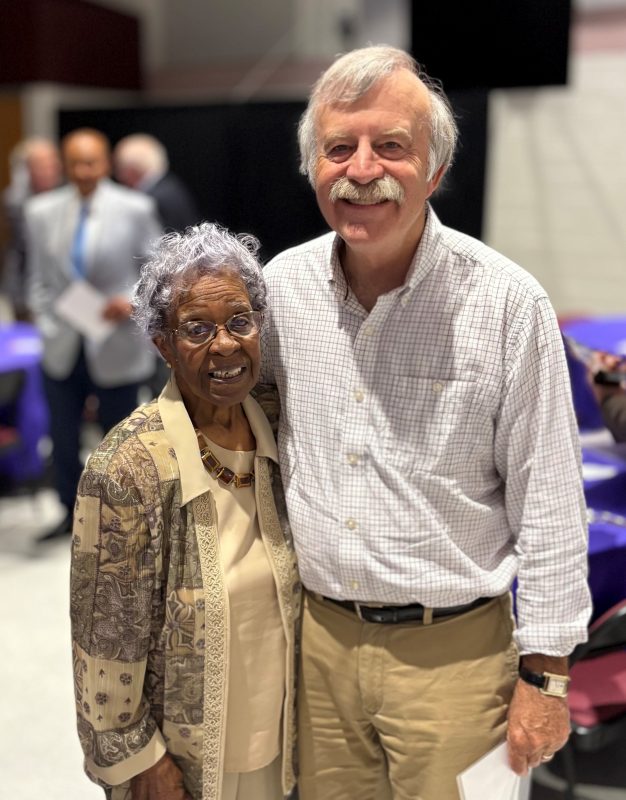

In addition, Virginia Tech’s Institute for Policy and Governance (VTIPG), a share of whose faculty and graduate students have been engaged with the Calfee Center during the last two years as they have investigated the Training School’s powerful role in educating Black students to excellence despite doing so in the midst of systemic oppression and inequality, has named Venable the first recipient of the Institute’s new annual Award for Moral Imagination and Courage.

According to her former students, that honor is well deserved. They recall how she turned the entire day into a learning experience in the pursuit of excellence, whether it had to do with reading, writing or learning how to tell time. As Dr. Mickey Hickman, who today serves as president of the Center's board of directors recently recalled, "When you came in the entrance of Calfee Training School, above the main door was a big clock. She would send us out at different times during the day—sometimes she would send us out as a team—and then we would come back and report to the class what time it was. She was fun, always smiling and you felt safe, and you felt loved."

Venable established early in her teaching career that in her class, the primary goal was to ensure that by the time the school year ended, every student would not only be able to read, but to enjoy reading as well. That's why when each new group of students arrived on the first day of school, they found their teacher sitting in an old-fashioned claw-style bathtub situated in the middle of their classroom— reading a book.

As her pupils gathered around, Venable explained that she was able to sit in the tub because she knew how to read. And when they reached specific goals during the year, they, too, would be able to enjoy a book within it. Or, if the tub was already occupied, Venable also repurposed a refrigerator box into a carpeted reading room that her students also came to covet.

Venable’s strategy was overwhelmingly successful and was emblematic of her many efforts to dignify the worth of each of her students and to encourage each to realize their capabilities as fully as possible, despite the confining social strictures of the time.

The Calfee Training School officially closed in 1966 as part of Pulaski’s desegregation process. Venable transitioned to serve on the staff at Jefferson Elementary in the County, although she was the lone Black Calfee teacher to do so, as many of her colleagues were not deemed academically qualified and were instead offered teacher aide or other classified positions.

Venable said she encouraged administrators in the late 1960s and early 1970s to reconsider their action, even becoming involved with NAACP-led initiatives to press for change. Many of her colleagues, as well as members of the community, were not happy with her activism, but she had always been encouraged to fight for what was right, and believed she was doing so, thus remained undeterred:

My father was a very strong man, even though he was uneducated, but he was the smartest man I've ever met in my life. His philosophy was one must stand up for what you believe in, you must stand your ground.

As Venable remarked in a recent interview, "You're not there for the school board, you're not there for the principal, you're not there for the other teachers. ... You're there for those little people who have been entrusted to your care."

VTIPG Director Max Stephenson Jr. observed recently when conferring Ms. Venable the first annual Institute award for Moral Imagination and Courage that,

When we spoke with you and with alumni who had experienced your teaching and mentoring first-hand, we learned of the many ways you encouraged your students at Calfee to ‘imagine their lives and futures otherwise’ despite the unjust conditions in which they were living. In so doing, you daily modeled for those children, and indirectly for their families and your colleagues, your profound belief in their innate dignity and in the possibility those youngster’s lives represented. Importantly, they never forgot how you persistently sought to encourage each of them to develop their talents and pursue their dreams. In a word, we learned that your mark on their lives has proven indelible. … Just as significantly, we discovered that you often persevered in your chosen ethical course even when, or perhaps especially when, that path proved professionally or personally fraught. In our view, you consistently exhibited an indefatigable willingness to engage with the social paradox that ever befalls the just; they constitute, as Alan Jacobs, Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Baylor University has memorably remarked, a community “whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere.” That is, they are deeply anchored but always open to others; keen, but ever receptive to learning and to new experiences and relationships. The Institute is delighted to celebrate your enduring belief in education, imagination and democratic possibility and your life-long pursuit of the morally just. It is our honor to salute you in this way.