After Cairo 2050: The Spatial Politics of Regime Security in Umm Al-Dunya

ID

Reflections

The popular mobilization that brought the resignation of Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, on February 11, 2011, injected new hope among many of that state’s citizens, especially those in its sprawling capital, Cairo. While many believed Mubarak’s removal would result in a transformed city, government and country, this brief article traces the continuity of Mubarak-era urban plans for Cairo. I argue each of the three successive administrations following Mubarak’s fall—those of Mohamed Tantawi (2011-2012), Mohamed Morsi (2012-2013), and Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi (2013-Present)—adopted strategies outlined in the Cairo 2050 masterplan, first released by Mubarak’s government in 2008.

This continuity in urban management goals and practice suggests that, despite the revolution and different administrations, Cairo urban planning continues to be guided largely by priorities and logics first articulated during the Mubarak years.

Cairo as Gauntlet and Proposed Solutions

Cairo, home to more than 20 million inhabitants, is characterized by “high population density, traffic congestion, continuous increase of unplanned and unsafe areas [informal settlements], high air pollution rates and other environmental problems” as well as the intense urban sprawl beyond the Nile River Valley that creates and accompanies these conditions (MHUC & UN Habitat, 2012, p.10). The ever-expanding borders of the city have contributed to, and generated, a range of issues, including fast growth in informal housing, overburdened and often inadequate water and sanitation systems, overcrowded transportation infrastructure and the sprawl of “ghost” cities beyond the Nile River Valley, among others.

These deeply interwoven issues constituted some of the kindling that eventually led to mass mobilization to oust Mubarak from office.

The General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP) office in the Ministry of Housing first released Cairo 2050, a 200-page document outlining a master plan for the city, in 2008.

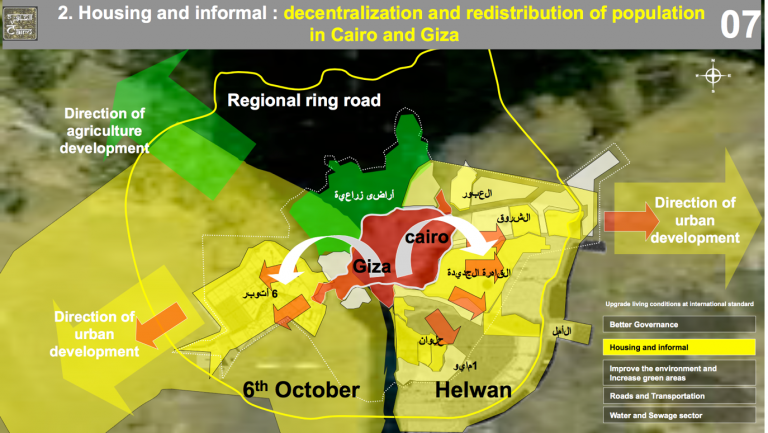

The foundational principles of that vision were “decentralization” and “de-densification.”

The Mubarak administration pursued these objectives through “megaprojects;” large-scale “priority developments of regional and national importance (GOPP, 2008, p. 36).” These included relocation of government ministries and public institutions to areas beyond the city’s core (GOPP, 2008, p.36). While the Mubarak administration succeeded in developing the Six of October City and New Cairo megaprojects outside the boundaries of Cairo, the major ministry buildings—many that would-be sites for protest in 2011—were never relocated, perhaps due to the financial crisis of 2008 or the competition of other priorities.

The Mubarak administration employed public-private partnerships to lure Persian Gulf state investment as the fuel to expand the city. Indeed, by early 2012, half of the 26 most valuable real estate developments in Egypt were majority-owned by Gulf-based conglomerates (Deknatel, 2012).

Post-Revolution Urban Management of Cairo

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) administration shifted the focus of the city’s planners from Cairo’s periphery to its urban core as they sought to manage post-Mubarak Cairo. Mohamed Tantawi’s SCAF erected concrete barriers around the Interior Ministry and police stations throughout the traditional core of the city. The military also actively regulated population flows in and out of centrally located Tahrir Square, particularly in the aftermath of the Mohammed Mahmoud Street standoff between Egyptian police and protesters that resulted in the deaths of 40 people in November 2011.

The June 2012 transition to civilian rule following the election of Mohamed Morsi to Egypt’s Presidency, brought new salience to the Cairo 2050 masterplan. The Morsi administration maintained many of the walls erected in downtown areas during the SCAF era and also embraced Mubarak-style megaprojects once more. For Morsi’s government, the showcase piece was the Nahda project, whose architects promised would “redistribute the population density of Egypt’s 80 million to 90 million people” and “get out of the Nile Delta Valley to new regional growth areas (Deknatel, 2012).” The government did not realize these aims as it was removed from office in the Egyptian Armed Forces coup d’état in July 2013.

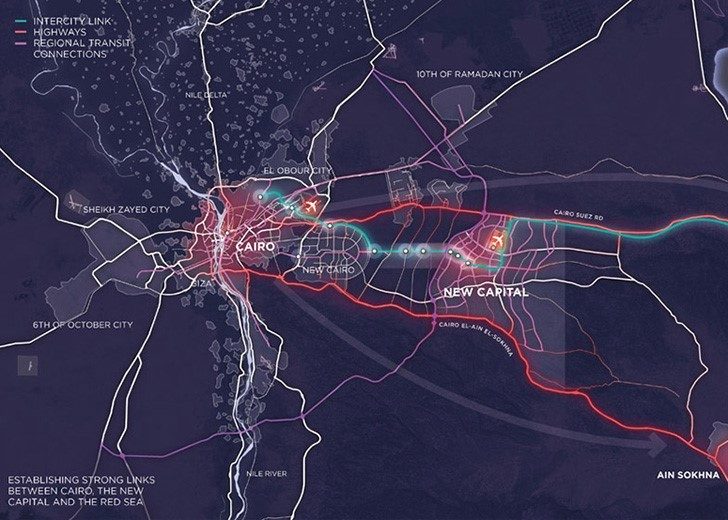

For its part, the Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi administration announced two megaprojects on a scale that dwarfed Mubarak’s earlier aims: a Suez Canal expansion and a “New Cairo” Capital City. Al-Sisi’s public 2014 announcement of planned construction of an additional lane for the canal led to a series of contracts with European, Persian Gulf and American companies to collaborate with Egypt’s Engineering Authority of the Armed Forces to dredge for the expansion (Kalin, 2014).

The New Cairo Capital City, announced in early 2015, fostered still more vigorous economic ties with China, Egypt’s largest trade partner, and looks set to contribute to additional sprawl in its planned location, twenty-eight miles outside of the city in the eastern desert (Kirk, 2016). China’s state-owned construction company has pledged $15B, and the China Fortune Land Development Company has pledged $20B to help to underwrite the proposed effort. Egypt must still raise its own share of the funds needed, an additional $10 billion (ibid.). Construction has begun. If completed, this new city will be located beyond the fertile Nile River Valley, prompting questions of whether sufficient water, sanitation and basic infrastructure can be made available to sustain it in systems already operating beyond their design capacity.

The new Capital City and Suez Canal expansion initiatives garnered headlines for the new administration and helped to shore up its legitimacy with Egypt’s residents, even as each effort helped the state expand its financial ties and networks in tough economic times.

The Cairo Capital City project also embraced the Mubarak-era goal to move the state’s principal ministries to the periphery of the city to make it more difficult for residents to mount major protests at them. The al-Sisi administration moved the symbolically contentious Interior Ministry to New Cairo in April 2016. All other major government ministries are slated to follow suit and will eventually be moved to the new Cairo Capital City on its completion between 2020 and 2022.

Regime Security and Management of Cairo

The continuity in aspiration and content across the otherwise disparate recent Egyptian regimes highlighted here, points to close connections between urban planning and leaders’ perceptions of the security of their rule. While it would be too reductive to suggest that Egypt’s leaders’ self-interest alone has driven Cairo’s planning choices across the four administrations, there is little doubt that this motive appears and strongly, in their selected means to manage the city.

The various regimes’ attempts since Mubarak’s fall to manage Cairo through continued sprawl and internal partitions reveals the intimate relationships between space and power across geographies, institutions and the wider society. Power is always situated in space, and this brief examination of development and development policy in Cairo has sought to foreground the material manifestations of regime power. However, the nation’s mass mobilization during 2011 reminds analysts that the regime’s power is never absolute. Given this reality, it becomes possible to conceive of the projects of the recent successive Egyptian national government administrations less as arbiters of absolute control and power over land use and populations and instead, as evocations of the fear, insecurity and uneasiness within which their rulers have operated. Cairo’s stubbornly persistent urban transformation plans—both imagined and achieved—reveal more about the fears and psychoses of those leaders than about whether any of the efforts conceived might actually better serve the Egyptian citizenry.

References

Allam, Hannah (2 Feb 2011). “Wednesday’s Crackdown was Vintage Mubarak,” McClatchy Newspapers. Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): http://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/world/article24610057.html

Bel Trew, Mohamed Abdalla, and Ahmed Feteha, (9 Feb 2012). “Walled in: SCAF’s Concrete Barricades,” Ahram Online. Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/33929/Egypt/Politics-/Walled-in-SCAFs-concrete-barricades-.aspx

Cambanis, Thanassis (24 Aug 2010). To Catch Cairo Overflow, 2 Megacities Rise in the Sand,” The New York Times. Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/25/world/africa/25egypt.html

Daily News Egypt (19 Jan 2017). “Impact of Egypt’s Mega Projects Revealed at Cityscape Business Breakfast,” Daily News Egypt. Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): http://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2017/01/19/impact-egypts-mega-projects-revealed-cityscape-business-breakfast/

Deknatel, Frederick (31 Dec 2012). “The Revolution Added Two Years: On Cairo,” The Nation. Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): https://www.thenation.com/article/revolution-added-two-years-cairo/

General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP) (2008). Cairo 2050 Vision.

Kalin, Stephen (18 Oct 2014). “Egypt Signs with Six International Firms to Dredge New Suez Canal,” Reuters. Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): http://www.reuters.com/article/us-egypt-suezcanal-idUSKCN0I70IC20141018

Kirk, Mimi (13 Oct 2016). “Egypt’s Government Wants Out of its Ancient Capital,” CityLab – The Atlantic. Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): http://www.citylab.com/politics/2016/10/egypt-cairo-capital-city-move/503924/

Kennedy, Merrit (30 Mar 2012). “To Keep Protesters Away, Egypt’s Police Put Up Walls,” NPR. Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): http://www.npr.org/2012/03/31/149727510/to-keep-protesters-away-egypts-police-put-up-walls

Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities (MHUC) & UN Habitat (2012). “Greater Cairo Urban Development Strategy.” United Nations Habitat. Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): https://unhabitat.org/strategic-development-of-greater-cairo-english-version/

Rios, Lorena (2016). “Egypt’s Capital Mirage,” Roads and Kingdoms. Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): http://roadsandkingdoms.com/2015/egypts-capital-mirage/

Sims, David (2011). Understanding Cairo: The Logic of a City Out of Control. The American University in Cairo Press. The Capital: Cairo (2015). Available at (Accessed 9/10/2017): http://thecapitalcairo.com/

Rob Flahive is a second-year PhD student in the Alliance for Social, Political, Ethical and Cultural Thought (ASPECT). His research focuses on tensions in the preservation of international style architecture in North Africa, the Middle East and East Africa. He holds a Master of Arts in Political Studies from the American University in Beirut and a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature from Washington University in St. Louis.

Rob values learning from personal experience as well as from conversations with others possessing different perspectives. He cannot imagine life without espresso, pizza (manoushe) or Fairouz.

Publication Date

September 14, 2017