Curating the Spectacle of a “Decolonized Vision” at the Royal Museum of Central Africa: Rethinking the Inheritance of Colonial Museums

ID

Reflections

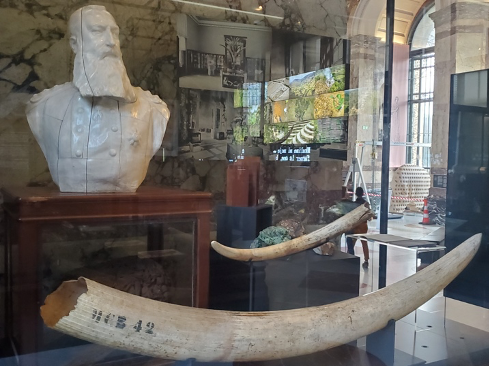

“Everything passes, except the past” is emblazoned on the wall of the long, whitewashed underground tunnel between the sleek postmodern two-story glass Welcome Pavilion and the neoclassical Royal Museum of Central Africa (RMCA) complex in Tervuren, Belgium. The RMCA is a repository for the racialized violence of Belgian colonialism in Central Africa from the late 19th century to the middle of the 20th century. King Leopold II (1835-1909) initiated construction of the neoclassical building as the “Colonial Palace” to house what he intended to be the World of Colonialism School in 1905 (Silverman, 2015). This plan built on the large number of visitors that descended on the eventual grounds for the 1897 World Exposition that featured plundered objects from Leopold II’s personal dominion of the ironically named Congo Free State (1885-1908). The RMCA was established on the Tervuren grounds to showcase “ethnographic” items originally displayed in the “Congo Pavilion” of the Exposition (Silverman, 2015).

The “past” referenced by the RMCA’s entrance aphorism recalled the horrific injustices of Belgian rule of the Congo during King Leopold II’s notorious reign. Hochschild has estimated that approximately 10 million Congolese died as a direct or indirect result of torture, maiming or murder by their Belgian overseers when they were unable to meet ivory or rubber harvest quotas (Hoenig, 2014). Yet the violence was not limited to Congo. As part of the 1897 World Exposition, sections of the eventual RMCA grounds were temporarily converted into a “human zoo” in which 267 imprisoned Congolese men, women and children were displayed—seven of whom died of exposure during the event (Hassett, 2020).

The RMCA whitewashed the histories of racialized violence of Belgian colonialism from its official opening in 1910 until the early 2000s (Royal Museum of Central Africa, 2020b). The shift that began to occur in the Museum vision and operation at the start of the first decade of the 21st century was a product of several historical factors. That turn was a result of the influx of Congolese to Belgium with the deterioration of political and economic conditions in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the 40th anniversary of the DRC’s independence in 2000 and new scholarship on the brutal legacy of Belgian colonialism in that nation (Bragard, 2011; Silverman, 2015). Despite widespread racial discrimination faced by former Congolese in Belgium, their increased presence raised the visibility and salience of an ongoing scholarly and public debate concerning the historical relationship between Congo and Belgium (Bragard, 2011; Demart, 2013). This turn was complemented by American journalist Adam Hochschild’s history of the violence in Congo Free State in King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (1998) and Belgian sociologist Ludo De Witte’s history of Belgian complicity in the assassination of Congo’s first Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in 1961, De Moord op Lumumba (1999; Silverman, 2015). These events began to reshape Belgium’s relationship to Congo and the country formally apologized for its role in Lumumba’s death in 2002. This fresh analysis of past behavior also occasioned a hard look at the orientation and foci of the RMCA, which had remained largely unchanged since its opening in 1910.

The transformation of the RMCA was initiated by the state appointment of a new Director, Guido Gryseels, in 2002. Under Gryseels leadership, the Museum collaborated with the Comité de Concertation MRAC-Associations Africaines (COMRAF) to integrate materials from Hochschild’s text as it undertook an extensive review of its orientation and operations during the first decade of Gryseel’s tenure. This effort to begin to recast and revisit its collections also included a decision to highlight the work of current Congolese artists (Van Bockhaven, 2019). The first exhibit to showcase this evolving vision was the “Memory of the Congo” (2005), which, while it was advertised as an “inclusive” multidisciplinary and multimedia approach, was nevertheless criticized by art historian Debora Silverman as a “tepid and reluctant revisionism” of Congo Free State history that downplayed the forced labor and racialized violence of the colonial era (2015, p. 630).

These nascent changes in thinking and direction, however mixed in their outcomes, set in motion what would eventually become an extensive 83 million Euro renovation of the RMCA between 2013 and December 2018. The Museum’s reopening coincided with a recalibrated aim of “present[ing] a contemporary and decolonized vision of Africa in a building which had been designed as a colonial museum (Royal Museum of Central Africa, 2020a).” This ongoing attempt to reorient the institution’s aims has begged the question: To what extent is it possible for the RMCA, a colonial museum established through racialized injustice, to advance a “decolonized vision of Africa,” as it now seeks to do? This is not a question confronted by curators and administrators of the Royal Museum of Central Africa alone. Despite the claims of its Director that the RMCA is the “last colonial museum in the world,” such institutions, sometimes rebranded as “ethnographic” museums during the 20th century, exist throughout Europe. Examples include the Tropen Museum in Amsterdam, Volkenkunde in Leiden, Museu do Oriente (Lisbon) and the World Museum in Vienna (Brown, 2018).

In what follows, I argue that the “decolonized vision” asserted by the RMCA amounts to a spectacle that simply reorganizes power without confronting the foundational issues that underpin the very idea of the institution or its collection of objects. Nonetheless, I also contend that while the animating conceit of a “colonial” museum may be irredeemable, it is not without a critical purpose in encouraging visitors and analysts alike to ponder, and possibly, in consequence, to chart, more equitable futures.

A “Decolonized Vision” in a Colonial Museum?

Congolese artist Chéri Samba’s painting “Reorganisation,” commissioned in 2002 by Director Guido Gryseels, encapsulates the tensions central to the RMCA’s “decolonized vision.” The realist oil painting portrays a tug-of-war over the infamous “Leopard Man” sculpture commissioned by the Belgian Ministry of the Colonies in 1913 and on display in the Museum (Van Bockhaven, 2009). That sculpture depicts a member of the Congolese Leopard Men society, categorized as a “subversive” group by colonial authorities, holding steel claws and wearing a Leopard skin hood, preparing to murder a sleeping man from another Congolese faction (Silverman, 2015). The sculpture reflects a broader trend of negative associations of murder, “savagery” and even cannibalism with the Leopard Men group by Belgian colonial authorities (Van Bockhaven, 2009). This depiction was replicated in Belgian pop culture when the Leopard Men were featured villains as well as adversaries of the wildly popular comics character Tintin in Tintin au Afrique in the 1930s (Van Bockhaven, 2009, p. 80).

Samba’s painting captured the ethical tensions of displaying dehumanizing representations of the Congolese in the RMCA. Curators at colonial museums are persistently faced with the question of whether such objects premised on racial subjugation and extreme violence should be placed on display. In Samba’s painting, the white RMCA staff, situated at the institution’s entrance, tug on a set of ropes attached to the figure while members of the Congolese diaspora and Belgians of African descent seek to pull the sculpture down the Museum’s stairs and away from its central building (Hassett, 2020; Van Bockhaven, 2019). In the painting, Gryseels, in a suit, stands behind the tug-of-war on the stairs of the RMCA, looking not at the struggle, but directly at the viewer.

The struggle over the “Leopard Man” sculpture depicted in Samba’s painting speaks to significant changes in Belgium since the Royal Museum was established and to still broader questions linked to what European societies should do with these colonialist institutions. Should colonial museums be shuttered? What should be done with their plundered objects? Should those items be returned and now offensive dehumanizing representations of previously subjugated peoples be destroyed? How can museums contribute to a deepened understanding of the legacies of past violence and its effect on the present without perpetuating the racialized assumptions and cruelty characteristic of the colonial era? The tug-of-war in Samba’s evocative painting gestured toward these questions, and in some ways, reflected—or perhaps set in motion—some of the changes at the RMCA.

Yet for all of the important discussions and potential changes Samba’s painting provoked, the spectacle of both the painting and massive renovation of the museum has had a curious effect akin to what Mitchell has dubbed the “world as exhibition” (1988, pp. 14, 20-21). For Mitchell, the world as exhibition was a technique of representation that used the spectacle of a specific representation, such as Samba’s depiction of tensions concerning the provenance and dehumanizing representations of Congolese, as a framework to produce certainty that those ethical tensions extended beyond the canvas.

However, the RMCA renovations seem more invested in the spectacle of the ethical tensions of the museum and its renovations, rather than in confronting the deeper ethical questions latent in displaying “Leopard Man” and other dehumanizing statues. For example, Gryseels posed with a replica of the Reorganization painting at the RMCA’s reopening in December 2018 (Van Bockhaven, 2019). For all of the tensions portrayed in Samba’s painting and the abiding questions they raised concerning representation of the horrific legacy of Belgian colonization, the actual “Leopard Man” sculpture and other dehumanizing sculptures of Congolese remain on display today with minimal accompanying explanation, in the Museum’s “sculpture depot,” just a few feet away from Samba’s painting. Ironically, Samba’s painting became part of what the RMCA has fashioned as its “decolonized vision of Africa.” The Museum today formally offers a narrative that suggests that it realized this “decolonized vision” and dealt adequately with the ethical concerns raised by its history via its renovation. Yet there are a lot of issues with this narrative.

As noted above, the RMCA has formally advanced a decolonized vision comprised of two principal elements. First, its leaders have sought to present a “critical narrative” of the colonial history of Congo through new captions, reorganized exhibit spaces and new installations that reframe existing objects. Secondly, the Museum now curates work of currently-active Congolese and African artists on an ongoing basis (Hasset, 2020, p. 27).

New placards in the Colonial History and Independence Room offer insights into the perspective that informed the renovation. The Congo Free State information display, for example, now explains that “The conquest of the region, the subjugation of the population and the exploitation of, in particular, ivory and rubber [were] accompanied by large-scale violence. There [were] protests against this at home and abroad” (Royal Museum of Central Africa, 2020c). This sanitized acknowledgement of widescale violence does not include figures, but is surrounded by colonizer artifacts, such as hats, documents and photographs in a room with a massive mural of Africa showing Belgian expeditions between 1816-1900.

A nearby Colonial History placard acknowledges the difficulties for the Museum of the colonial history of its collections. These were “composed by Europeans” and thus it remains a challenge to “tell history from an African perspective”, despite the fact that such histories would be accessible via Congolese or African historians (Royal Museum of Central Africa, 2020d). Moreover, the social malignancies of the colonial past are agreed upon by historians, but the subject remains a “very controversial period” for the Belgian public (ibid.). In this context, the RMCA now seeks to “stimulate interest in this period and to be a forum for lively debate” on the legacies of Belgium’s colonial past (ibid.). Yet, notably, debate, by itself, does not effectively alter systems of power. Instead, and at best, it can provide a confined and relatively peaceful space for such contestation.

A separate element of the Museum’s approach to a decolonized vision has been to extend the historical and topical range of the works it exhibits. Whereas the RMCA previously focused solely on representing Central Africa through depictions of its landscape, biodiversity, rituals and ceremonies, languages and ethnography, the updated displays now also include information on the region’s land, resources and music. The reorganized RMCA also offers a revised approach to the rituals and ceremonies of those native to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The rituals and ceremonies section, for example, now features large screens with videos of individuals offering oral histories and interpretations of specific nearby objects related to Death and Commemoration or to Education. The inclusion of these commentaries offers a different and less sterile approach to curation. Moreover, this step reflects a clear aim to expand the perspectives portrayed in the space beyond those of Belgians (past or present).

The extension of the narrative and the inclusion of new voices constitutes one step in an urgent process to confront previous sanitized histories of colonialism, yet the question is whether it is enough. Sociologist Gurminder Bhambra (2014) has called for efforts to forge new historical connections that reframe whitewashed histories of colonialism. However, she has also argued that such an expanded frame with more voices is not by itself a sufficient remedy to address past injustice. A further step is needed, that of analyzing precisely “why” colonial histories were occluded and what that means for (in her case) Sociology. In other words, greater inclusion is a starting point to a much larger and still more uncomfortable project of probing historical injustices as they continue to ramify and affect the present.

Roy (2016) has extended Bhambra’s (2014) approach to the “silenced” histories of colonialism in her own field of urban studies by calling for “new geographies of theory” aimed at “inhabiting” the prevailing eurocentrism of the discipline in order to thwart it (2016, p. 207). Both authors have called for additional actions beyond the important preliminary step of expanding the range of voices, histories or stories told. Both have asserted a need for European and American societies to reckon with why exclusions occurred and for deep consideration of the enduring effects of those omissions, a challenge not yet taken up by the RMCA.

Rethinking the Potential for Curating Injustice

So, what would a potentially decolonized vision of Congo, or more broadly of Africa, entail? Indigenous studies scholars Tuck and Wang (2012) have contended that decolonization cannot be a metaphor, because the term relates to a specific process of foreign settlers returning stolen land to indigenous populations. Thus, the Museum’s reference to a decolonized vision amounts to what they refer to instead as “settler mov[es] to innocence” (2012, p. 9).

These “moves to innocence” are “strategies and positionings that attempt to relieve the settler of feelings of guilt or responsibility without giving up land, power or privilege, without having to change much at all” and ensuring “settler futurity” at the expense of “indigenous” futurity (Tuck and Wang 2012, pp. 9-10). In other words, to assuage guilt, one invokes terms such as “decolonized vision” or to “decolonize” and in so doing, maintains the status quo that colonialism produced.

The moves to innocence argument provides a framework for understanding the Museum’s efforts to change its vision and foci. Tuck and Wang’s (2012) critique also implies the need for the Belgian government to provide restitution for the objects now housed at its Royal Museum. For its part, the RMCA has partnerships with museums in Senegal, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda. However, its literature notes that it, “has not received any formal requests for restitution, but is willing to enter into dialogue with national museums of the countries concerned (Royal Museum of Central Africa, 2020e).”

At the 2018 reopening, Gryseels offered a revealing response to a question concerning restitution. He invoked the need to ensure greater “access” to the current collections, because “Congo, at the moment lacks capacity to deal with that heritage,” a claim that echoes responses to questions of restitution at the British Museum (Ridgewell, 2018). Such claims, justified or not, ensure the “futurity” of a reorganized, but minimally altered institution that does not take the step beyond using the “controversy” as a spectacle that assuages guilt and thereby maintains the status quo of power relations within the Museum and beyond.

Ultimately, the RMCA and other colonial museums are, in principle, “irredeemable” in the sense that they can never move beyond their indicted foundations (Green 2018). Regardless of how many renovations or reorganizations the RMCA completes, it will always be a colonial museum because colonialism is built into the stones that comprise its walls. Indeed, that structure, it must be said, was paid for by the genocidal violence perpetrated against the population of the Congo Free State that continued in lesser forms throughout the history of the Belgian Congo (1908-1964). If this is so, what, then, is to be done with the RMCA and other museums like it?

Wayne Modest, Director of the Research Center for Material Culture for several colonial museums of the Netherlands, has referenced the “heavy work” of reckoning still ahead for such institutions. As he has observed, colonial museums are the product of:

… histories that were bequeathed to us, we didn’t want them, we prefer if we didn’t have them. We benefit from the good parts of them, but sometimes we don’t want to acknowledge the bad parts of them, but we are a part of this history that created them (THNK, 2015).

Modest’s remarks suggest that museums’ acknowledgement of connections to histories of racialized violence and plunder constitutes a starting point, not an end point, in addressing those legacies. Much like Bhambra and Roy, Modest has pointed to the need for colonial museums to define themselves as sites in a constant process of confronting the violence of the past, rather than arguing they can do so completely via a discrete set of actions, as the RMCA renovation would have its visitors believe. When asked what constitutes “decolonizing” in an interview in 2018, Modest responded that he did not like the term, but would rather think of “decolonizing” as a process, an unresolved aspiration, toward which colonial legacy institutions and societies should persistently strive (Green, 2018). He went on to explain:

I like the use of the ‘ing,’ because it [decolonizing] indicates that it is a future practice, that it is a labor, a burden, it is something that one should work at all the time, and that one should not celebrate that one is there yet (Green, 2018).

The implication of this formulation is that one never reaches the “there” of a “decolonized vision” in a previously colonizing society. Rather, it is an ongoing struggle. In this sense, the meaning and role of Belgium’s colonial museum, and its many counterparts, are in a constant process of being written and perhaps also, rewritten. That work is not now, and never will be, finished. Rather, Belgium’s colonial museum and other similar institutions should be seen as sites for critical forms of ongoing social and political curation, conversation, debate and research that simultaneously confront, reflect upon and undertake the heavy work of acknowledging the violence of the past while seeking to understand its portent for shaping the present and the future.

References

Bhambra, G. (2014) Connected Sociologies, London: Bloomsbury.

Bragard, V. (2011) “’independence!’: The Belgo-Congolese Dispute in the Tervuren Museum,” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, 9: 93-104.

Brown, K. (2018) “With a $84 Million Makeover, Belgium’s Africa Museum is Trying to Appease Critics of the Country’s Colonial Crimes,” Art Net. Available at: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/africa-museum-restoration-1408924

Demart, S. (2013) “Congolese Migration to Belgium and Postcolonial Perspectives,” Africa Diaspora, 6: 1-20.

Green, C. (2018). “Decolonizing Museums in Practice, Part III: Feat. Wayne Modest,” Anthropological Airwaves. Available at: https://soundcloud.com/anthro-airwaves/decolonizing-museums-in-practice-part-3

Hassett, D. (2020) “Acknowledging or Occluding “The System of Violence”? The Representation of Colonial Pasts and Presents in Belgium’s Africa Museum,” Journal of Genocide Research, 22: 26-45.

Hoenig, P. (2014) “Visualizing Trauma: The Belgian Museum for Central Africa and its Discontents,” Postcolonial Studies, 17: 343-366.

Mitchell, T. (1988) Colonising Egypt. London: Cambridge University Press.

Ridgewell, H. (2018) “Belgium Museum Tries to Exorcise Ghosts of Colonialism,” Voice of America. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xo19J8w2UxI

Roy, A. (2016) “Who’s Afraid of Postcolonial Theory?” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40: 200-209.

Royal Museum of Central Africa. 2020a. “Renovation.” Available at: https://www.africamuseum.be/en/discover/renovation

Royal Museum of Central Africa. 2020b. “Museum History.” Available at: https://www.africamuseum.be/en/discover/history

Royal Museum of Central Africa. 2020c. Placard: “The Congo Free State,” Colonial History and Independence Room.

Royal Museum of Central Africa. 2020d. Placard: “Colonial History and Independence,” Colonial History and Independence Room.

Royal Museum of Central Africa. 2020e. “Viewpoints of the Museum.” Available at: https://www.africamuseum.be/en/discover/myths_taboos

Silverman, D. L. (2015) “Diasporas of Art: History, the Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, and the Politics of Memory in Belgium, 1885-2014,” The Journal of Modern History, 87: 615-667.

THNK – School of Creative Leadership (2015) “Dr. Wayne Modest on How Guilt is Productive,” School of Creative Leadership. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7gQ5m_KC1Hg

Van Bockhaven, V. (2009) “Leopard-Men of the Congo in Literature and Popular Imagination,” Tydskrif Vir Letterkunde, 46: 79-94.

. 2019. “Exhibition Review: Decolonising the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium’s Second Museum Age,” Antiquity Publications, Ltd., 93: 1082-1087.

Robert Flahive is a PhD Candidate in the interdisciplinary Alliance for Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought (ASPECT) program at Virginia Tech. His research focuses on the tensions that arise in efforts to preserve architecture and urbanism produced through colonialism in Casablanca, Tel Aviv and Addis Ababa. He has an enduring interest in the intersections of the built environment and international politics as well as how individuals relate to wider social systems. He earned an MA from American University of Beirut and a BA from Washington University in St. Louis.

Publication Date

March 5, 2020