What Machine Kills Fascists? A Critical Reflection on the Political Power of Sound in the Trump Era

ID

Reflections

Introduction

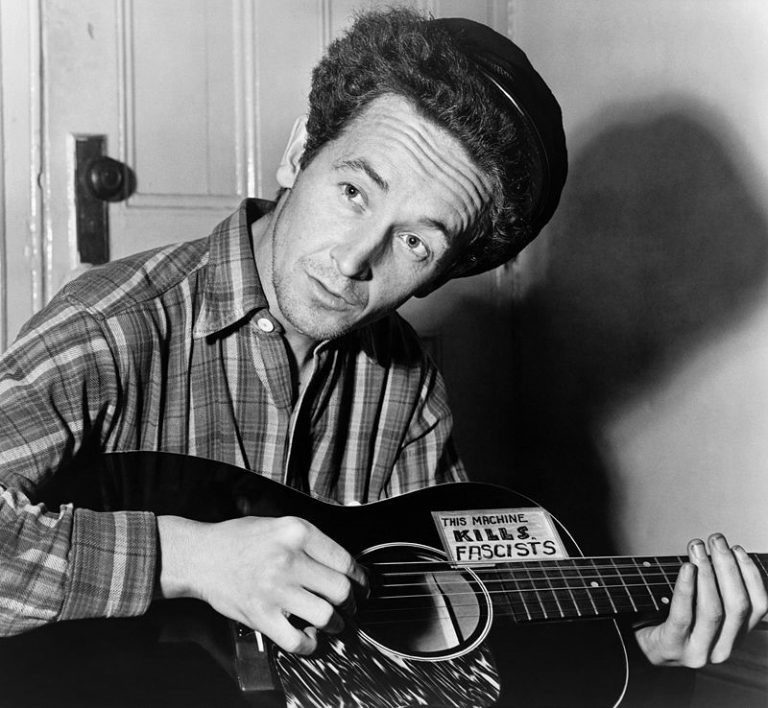

It is well known that the original writer of the song belted out by a David Bowie like-clad Lady Gaga, “This Land is your Land,2 during her Super Bowl 51performance on February 5, 2017 was the radical American songwriter Woody Guthrie. An iconic photo has preserved him for history holding a guitar with the words “This Machine Kill$ Fascists” in capital letters taped on its body above the strings. Indeed, this image is so well known that the Gibson guitar company has obtained a handsome return by replicating Guthrie’s 1945 Southern Jumbo model instrument complete with sticker3 (consumers may use it or not at their option) for a price of $2,429. The idea that a guitar or a song is a machine with the power to elicit violence, peace or productivity, continues to be a radical notion some seven decades after Guthrie sat for the famous photograph.

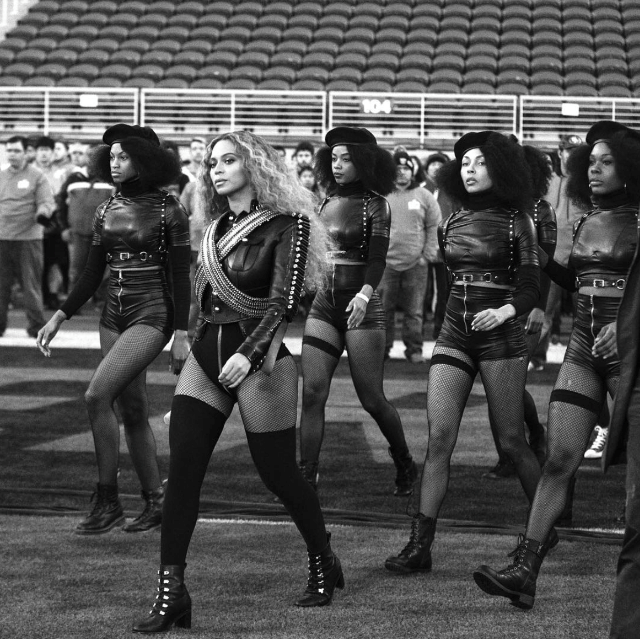

While teaching the course Southern Music: Music, Power, Place at Virginia Tech (Spring semester, 2017) the class’s students and I have discussed authenticity and another power of music; its capacity to create places. Conversations about music, specifically sound, as a national signifier have been difficult in our mediated age. Consumable performances and performers are much more highly sought after in recent years than strictly aural experiences in our nation thanks to live feeds, snapchat, instant replay and our cultural attraction to the visual. For instance, without the colorful drones that accompanied her, a knowledge of Guthrie’s politics and live tweeting commentary, many would have had a difficult time connecting only the sound of Lady Gaga’s performance to politics. This represents one example in which politics and the power of the voice have been usurped or made stronger by the visual, leaving listeners to ignore or fail to acknowledge the very powerful independent effects of sound. Another, and much more easily deconstructed example is Beyonce’s powerful Super Bowl 50 performance of “Formation” on February 7, 2016 from her critically acclaimed and extremely popular CD, Lemonade. The musical accomplishment represented by the album is undeniable; however, it was the visuals of the star’s performance at football’s annual great event that many citizens read as political.

A more personal understanding of the potential political power of sound occurred for me on January 22, 2017 when I rose at 2:30 a.m. to travel with a number of women and men from Blacksburg, Virginia to the Women’s March on Washington, DC. My trip was made possible through the generous donations of community members who wanted to be there, but could not participate and kindly made my attendance possible instead. To prepare, those attending made posters and I also purchased a t-shirt on which I wrote the message “Together Forward, Not One Step Back.” I also retrieved my red bandana from its storage place to wear in solidarity with the union miners and mountain top removal activists about whom I often teach. Those travelling together—myself included— did not, however, think about songs or chants we might use during the event. For me personally, this experience mirrored another that occurred just a few months earlier when I stood in solidarity on the steps of Burruss Hall with students concerned about attacks on immigration, acts of hatred being unrecognized and the need for increased resources for minority students at Virginia Tech and other universities. The irony, as we embarked on our sojourn to the March was, as at the previous event at Virginia Tech, we were seeking to be heard and recognized, an inherently sonic aspiration, but we were not at all mindful of that fact. As we began our trip, we imagined that our messages would largely be shared visually.

These two events, in combination with listening, voting, teaching, protesting, watching and analyzing popular performances, have led me to return to projects that first intrigued me during my initial semester at Virginia Tech in 2013. I was interested at that time in the vocalization of the political; that is, the political as expressed in sound. This essay relies heavily on those early research projects.

Indeed, this Reflection explores the voice as a space of resistance in the modern political schema. The questions I originally asked linked to this concern were: How does one account for a shifting, changing or evolving voice? How can voice be expressed in a way to free individuals from imposed identity(ies) and socio-cultural oppression? How do we become aware of what we cannot hear? How can we train our ears to listen? Mbembe has suggested that, “[s]uch research must go beyond institutions, beyond formal positions of power, and beyond written rules, and examine how the implicit and explicit are interwoven. . .” (2005, 69). There is much deeper research to be conducted on each of these concerns as well as actions to be organized to address them. The scope of this effort is admittedly limited and I welcome further conversations.

Sound

I use the terms “sonic” or “sonic spaces” to describe an area occupied by sound, which includes, but is not limited to the voice. Allegiances are spoken, nations are called to prayer and individuals also learn to exercise their ability to defend themselves by saying the word “no.” A multitude of studies have explored the intersections of politics and song and these have often received attention on nightly network news. Those reports have addressed, for example, Pussy Riot, T. Rex, Kendrick Lamar, Bono and U2, the Dixie Chicks, Wagner and recent Nobel Prize recipient Bob Dylan. Songs provide the rhythm and cadences for political movements and eruptions. My interest here is the voice as a political agent, captured by Michel de Certeau’s statement, “More reverential than identifying membership is marked only by what is called a voice, (voix: a voice, a vote) this vestige of speech, one vote per year” (1984, 177).

Robert Jourdain has defined voice, as “…two or more simultaneous, interrelated lines of music. Nearly all music consists of multiple voices, including a bass line, treble line and parts between” (1997, 343). For Jourdain and a number of other music scholars, voice is a means to a collective sound; music. For others, music is a means to engage in discussions, not of harmony and tonality, but instead of language and lexicons.

History of the Voice as Political

Music allows for communication beyond words and I propose that sound can catalyze changes beyond policy. This stance implies that the voice can serve as a micro and macro agent of change. Within my own area of study, the geographic and diasporic region of Appalachia, music is intrinsically connected to protest, and women, particularly, have often employed it as a tool of subversive activism. The Encyclopedia of Appalachia has described the links between music and the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s:

The Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s is the subject of several protest songs associated with Appalachia. Guy Carawan, while working at the Highlander Folk School, then located in Monteagle, Tennessee, in the late 1940s and the 1950s, reworked the old African American sacred songs ‘We Shall Overcome’ and ‘Keep Your Eyes on the Prize’ for striking textile and tobacco workers. Carawan’s version of ‘We Shall Overcome’ was adopted by Martin Luther King Jr. as the official theme song of the March on Washington, a central event in the 1960s phase of the Civil Rights movement. Carawan’s achievement is indicative of the influential stature and unquestionable dignity of Appalachia’s rich legacy of protest song. (Encyclopedia of Appalachia, http://encyclopediaofappalachia.com/entry.php?rec=55)

The gendered use of the voice in protest movements was also clear in the example of “Aunt” Molly Jackson, who performed “I Am a Union Woman,” “Kentucky Miner’s Wife” and “Dreadful Memories.” According to the entry treating her life in the Encyclopedia of Appalachia, “in 1931 she met with a delegation sent by the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners and subsequently traveled to New York City, “soon appearing before an audience of twenty-one thousand people” where she discussed living conditions in Eastern Kentucky and shared the songs noted above (“Aunt Molly Jackson,” Encyclopedia of Appalachia, http://encyclopediaofappalachia.com/entry.php?rec=121). The power of the female voice in leading public protest was also evident in Sarah Gunning’s “Down on the Picketline (1932),” Jean Ritchie’s “The L&N Don’t Stop Here Anymore” (1963) and “The Blue Diamond Mines” (1964), Malvina Reynolds’ “Clara Sullivan’s Letter” (1965), and Hazel Dickens’ “Clay County Miner” (1970), “Black Lung” (1970), “The Yablonski Murder” (1970) and “Coal Mining Woman” (c. 1970)5 These songs became anthems for securing better working conditions for the poverty-stricken workers of Appalachia (“Coal Protest,” Encyclopedia of Appalachia, http://encyclopediaofappalachia.com/entry.php?rec=55). This legacy of the voice in harmony, used to unify and to resist has been on my mind as I observe the current activist activities in the U.S. Jourdain has argued that the disruption of existing norms that these songs represented constituted, “violations of standard expectations [that] continue to be expressive” (1997, 313). But I wonder about protests today—how are we violating social expectations of expressiveness? How can we subvert standards of oppression, violence, dehumanization, etc. while also working outside the often oppressive norms of the popular culture, but within the realm of translation? How can we hold to a hope in the power of the voice and yet address meaningfully the frequent systemic voids in the collective? That is, how can we listen and identify what is missing in existing public understandings and expectations and norms?

Shifting the Focus from Eye-to-Ear

One must look no further than one’s television computer screen to notice the ways in which the feminine voice currently is subverting power. Between the 2017 Super Bowl half-time show by Lady Gaga and Beyonce’s Oshun inspired 2017 Grammy performance, issues of gender, class, race, systemic oppression, and the feminine have recently been highlighted on otherwise white, masculine, heteronormative, neoliberal stages. While Gaga appears tepid in comparison to Beyonce, and the powerful role of the feminine voice was evident, the privilege of the visual in both performances was striking. While the role of women in disrupting power through sound has continued into the Trump era, the means of message dissemination have changed. In a world which now communicates through screens, would those watching these events be able to hear the strains of activism present in these performances without the visual imagery with which each was presented?

Is it possible that our expressions are problematically visually centered? I believe so. Visuals can be misleading and easily manipulated. From crowd size to television programs, what one has seen and accepted previously is difficult to dismiss in our current era. Indeed, it may be that it is possible for sound to violate norms more easily than visuals can. That is, words may be more difficult to censor, manipulate and misinterpret. Sounds are less readily blocked out. Thinking of Foucault’s gaze, what if the way out of that theorist’s posited panopticon cannot be seen? (Foucault, 1975). What if it can only be heard and manifest through voice or vocal vibrations? I next briefly provide a few examples of this too often untapped potential of sound and voice.

- Sound supports. Walking back from the Women’s March to our buses, a man leaned out of an upper story window. He was nodding his head giving us a thumbs-up sign as we walked by. The memory is blurred, but I believe he was wearing a pink beaded necklace in solidarity. Soul-filled music poured out of his window; a female voice from an earlier era. Perhaps it was Nina Simone.

- Sound disrupts. As we walked back to the buses too, I stopped, and asked my friends, “Do you hear that?” Playing very clearly, hovering above the marchers returning to their homes was country western singer Toby Keith’s retaliation-driven anthem “Courtesy of The Red, White and Blue (The Angry American).” I did not hear the performances during the march, but rather was swept up in the drums, songs and chants around me. Keith’s hyper-masculine voice echoing was not the disjuncture I expected, but it nonetheless reminded me of the power of sound. Ambulances. Whistles. Arguments between neighbors on the other side of a wall. These sounds also routinely disrupted us as we walked and marched and we often found ways to tune them out, but, our experience in Washington convinced me that even one’s best efforts are almost always inadequate to that challenge.

- Sound gathers. At varying points during the March our large group was swept up, moving apart in a sea of pink hats and posters. One marcher held an American flag high in the air—I would search for it and know my group was not far. When the crowd grew too thick to spot the flag, our group began chanting “LET’S GO HOKIES” and found one another by doing so, much to the interest and annoyance of some of our fellow marchers.

One lesson I took away from my participation in the Women’s March is that sound must be consciously wielded. A final anecdote illustrates this point. A few months ago, a group of students stood on the steps of Burruss Hall, as I recounted above, and chanted, ‘This is what democracy looks like.” Cameras gathered in front of those students, who were seeking to be heard and recognized. That is, paradoxically, even in the powerful raising of voices together, the protester’s chants privileged the visual, and sought visual recognition. The look of democracy was also emphasized—yet the chants were all the same. Is this what democracy sounds like? What does democracy sound like?

Conclusion

The ability of the feminine to render its needs via collective voice, and the capacity and willingness of a patriarchal system to listen to those claims, translate and hear them, are interwoven in problematic ways. At the March on Washington, participating women were seen through images distribute by friends and family on social media, creating a powerful mirroring of personal politics and judgments. However, and again paradoxically, the intersectional claims raised by those gathered were largely lost in the translation of stories and voices to images “liked,” shared and replicated. I am not arguing that the March was not an igniting agent for a significant movement, but that our medium of sharing is immensely important, as often the media we choose (the visual), requires the literal and metaphorical removal of diverse and marginalized voices.

Even with its flaws, the Women’s March offered those participating and observing alike, a space to “sing.” Returning to Lady Gaga’s decision to bring Woody Guthrie’s song (if not his message), to one of the nation’s biggest stages, I wonder, is it possible that the power of individual and collective voice is too often overlooked today by those organizing public protests of various sorts? What can we learn from previous generations, and how can we best apply their methods of protest in an age of hyper-mediated sharing? How do we find harmony amid our new chaotic understandings of time and space? And most importantly, what labor must we do to attune our ears to the power of voices, especially those of women and of vulnerable populations more generally, to ensure that their interests and concerns receive attention?

____________________________________________________

Additional Readings

http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/the-music-donald-trump-cant-hear

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/11/arts/music/donald-trump-inauguration-performers.html

About the sounds of the Women’s March:

http://pitchfork.com/thepitch/1424-we-shall-overcomb-music-as-protest-at-the-womens-march/

Notes

1 Al Aumuller/New York World-Telegram and the Sun (uploaded by User: Urban) – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3c30859. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4945422

2 Please note I am only referring to her performance of “This Land is My Land,” not the lyrics of her controversial song “Born This Way.”

4 (http://www.vibe.com/2016/02/beyonce-boycott-formation-super-bowl/)

5 This list of performers is not exhaustive, but does reflect the massive body of relevant work women have produced.

References

“Aunt Molly Jackson,” Encyclopedia of Appalachia, 2013, Encyclopedia of Appalachia. 13 Dec 2013 http://www.encyclopediaofappalachia.com/entry.php?rec=121), Accessed February 14, 2017.

Butler, Judith, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Who sings the nation-state?: language, politics,

belonging. Seagull Books Pvt Ltd, 2007.

“Coal-Mining and Protest Music,” Encyclopedia of Appalachia, 2013, Encyclopedia of

Appalachia. 13 Dec 2013, http://www.encyclopediaofappalachia.com/entry.php?rec=55, Accessed February 13, 2017.

de Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Steven Rendall. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1984

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1975, esp. pp. 195-228.

Jourdain, Robert. Music, the Brain, and Ecstasy: How Music Captures our Imagination. W. Morrow, 1997.

Mbembe, Achille, “The Intimacy of Tyranny,” in Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin, Eds. (2nd ed.). The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. Oxford: Routledge Publishers, 2006, pp. 66-71.

Jordan Laney is a candidate for the Ph.D. in the Alliance for Social Political Ethical and Cultural Thought (ASPECT), with concentrations in social and cultural thought. Her dissertation research focuses on bluegrass music festivals as sites of identity construction. Jordan has been recognized as a Graduate Academy for Teaching Excellence (GrATE) Founding Fellow, Diversity Scholar (2014), is co-editor emeritus of SPECTRA: The ASPECT Journal and served as a Berea College Appalachian Sound Archives Fellow (2015-2016). Jordan’s research, teaching and service are informed by her experiences as a first -generation college student from the Appalachian region. She hopes to continue developing educational programs that critically examine the intersectional and hidden histories of rural areas to prepare communities for more just futures http://jordanlaney.com/

Publication Date

February 16, 2017