Who Speaks for the Farmer in the Green New Deal?

ID

Reflections

Introduction: The Green New Deal and the “Agricultural Sector”

On February 7, 2019, Senator Edward Markey (Mass.) and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (N.Y.) proposed companion congressional resolutions in their respective chambers that were collectively known as the “Green New Deal.” While such legislative acts lack the force of law, the Green New Deal proposal marked a historic turn in the United States Congress’s attention toward the issue of climate change and its language anticipated significant policy changes that would affect all sectors of the U.S. economy. Most boldly, the resolution sought to combine sustainability goals with an attempt to address systemic injustice in the U.S. As someone currently working with lawmakers to enact legislation protecting small farmers in my native state of Maryland, I was especially interested in the subsection of the text that addressed how the “agricultural sector” would be transformed. The resolution called for the following:

Working collaboratively with farmers and ranchers in the United States to remove pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector as much as is technologically feasible, including—(i) by supporting family farming; (ii) by investing in sustainable farming and land use practices that increase soil health; and (iii) by building a more sustainable food system that ensures universal access to healthy food (H.R. Con. Res. 109, 2019, pp. 8-9).

The vagueness of these goals is perhaps at once a curse and a blessing. Their lack of specificity assures supporters and opponents alike that these are not actionable steps with immediate implications. As a result, any legislation that follows this resolution will need to tackle these challenges with clearly articulated policy provisions. Moreover, it is not clear that the Green New Deal will accomplish either its sustainability or social justice goals by “supporting family farmers” as a collectivity. As matters now stand, a large portion of “family farms” in the U.S. (including organic ones) are currently undermining local food systems and destabilizing bioregional ecosystems in pursuit of profit. After reading the resolution, I was left wondering who exactly are the farmers that this Green New Deal intends to support, and will its adoption and implementation lead to sustainability and social justice?

Not All Family Farmers Wear Overalls (Just My Mom)

The phrase “family farm” may bring to mind a large white farmhouse surrounded by green cow pastures and corn fields, or perhaps Wendell Berry’s vision in The Unsettling of America of nuclear families living off the land, free from the nuisances of modern life (1977). My childhood serves as my own agrarian benchmark, helping my parents plant, harvest and sell our vegetables at our roadside stand. Nonetheless and despite its nostalgic connotations, these images bear little relationship to the large-scale farm operations that supply an ever-increasing proportion of our food in the U.S.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS), 98% of farms in the U.S. are “family” owned, but that percentage is misleading, as the ERS has defined the term as, “any farm where the majority of the business is owned by the principal operator—the person who is most responsible for making day-to-day decisions for the farm—and by individuals who are related to the principal operator” (2019, p.2). Within this definition, there is vast wiggle-room for additional non-family labor and absentee owner-operators who never touch the soil (white gloves instead of green thumbs). Large-scale “family farms” (those with sales of $1,000,000 or more per year) account for 45.9% of U.S. agricultural production, while medium-scale operations (those with sales between $350,000 and $999,999 per year) account for 20.6% of that total. Small-scale family farms (those with sales between $1000 and $350,000 per year) account for 21.1% of production. By the Department of Agriculture’s definition, non-family farms account for 2.1% of farms and 12% of production.

Farm size can be classified by revenue or acreage, although their market share is more easily seen with sales statistics, since a well-managed small property can be just as productive as a poorly managed large one. Gross sales vary greatly, from as little as $1,000 (the minimum to be considered a “farm” by the USDA) to $5,000,000. It is clear from statistical evidence alone that adding the word “family” to the term “farm” in the U.S. obscures the vast difference between the daily lives and operating costs of owners at different income and production levels. For this reason, any policy inspired by the Green New Deal that treats “family farmers” as a uniform, collective group will not address any existing systemic injustices. That is, such blanket policies will likely favor the interests of already well-capitalized large-scale farms at the expense of smaller ones.

Organic and Sustainable Production are Not Synonymous

The case of organic food production provides a useful illustration of how blanket government regulation coupled with the pressures of industrial farming have failed to address systemic injustice in the agricultural sector. Organic food is one of the fastest growing market segments in agriculture, and it is often posed as synonymous with sustainability. For this reason, it is similar to the label “family farm.” Both terms are often proposed as self-evident panaceas, as though “encouraging” (by carrot or stick) all family farms to become certified organic would magically “fix” the U.S. food system. As with most proposed utopian dreams, this solution has a dark side. As practiced today in the United States, organic farming is a far cry from its original implication of holistic sustainability. Indeed, one of the biggest issues with this form of production is its transportation footprint. It is not clear that a head of lettuce grown (certified) organically and shipped thousands of miles is better for human or planet health than the same grown “conventionally” on a farm near to where it is sold. In terms of transportation costs, for example, the major share of vegetables (including organic produce) in American grocery stores today travels an average of 1,500 miles from their farms of origin to their point of sale. Meanwhile, produce sold by smaller farmers in regional farmers markets and farm stands travels an average of roughly 60 miles to its final point of sale (Pirog and Benjamin 2003). This fact speaks for itself in terms of energy cost tradeoffs and the need for thoughtfully crafted policies.

As Guthman has argued, neither “organic” nor “family farm” inherently results in a sustainable agricultural system (2004). Guthman’s book traced the organic farming movement in California, from its hippie “back-to-the-land” beginnings to its present-day appropriation by large corporations keen on “greening” their image with consumers. Some two decades ago, a study of California alone found that the state exported approximately 485,000 truckloads of produce each year, with some of those travelling as far as 3,100 miles to their final point-of-sale (Hagen et al. 1999). Guthman contended that this export-heavy model had been adopted by large industrial farms, at the expense of nurturing diverse and accessible regional food systems.

In fact, the terms “family” and “organic” are today often used to describe many large-scale industrial farms that practice intensive monocropping and ship their produce thousands of miles. Even if the word “family” is dropped, large-scale “organic” agricultural operations raise other concerns. For example, General Mills announced in 2018 that it had contracted to convert an existing land parcel in South Dakota spanning 34,000 acres (53.125 square miles) called Gunsmoke Farm, to heavy organic wheat production with a (comparatively) small pollinator habitat. This move toward intensive organic cultivation is linked to growing consumer demand for such products, not necessarily to take better care of the earth. Nonetheless, some share of smaller farmers seeking to profit from the “premium” return organic food may command may now be priced out of the market by the glut of such products that General Mills (and others) are delivering.

Another and important piece of this puzzle is the fact that while organic may currently be an environmental “buzzword,” it is far from clear that its pursuit alone will transform our nation’s existing food system. The standard set by the United States Department of Agriculture for certified organic production, as Guthman has also argued, actually amounts to little more than a “no-go” (do not use) list of chemicals. Certified organic seeds, soil, compost and chemicals (i.e. pesticides, algicides, disinfectants and herbicides) also come with significantly higher price-tags than conventional inputs, creating a higher barrier of capitalization, and therefore of market entry, for growers. In contrast, the original goals of the organic movement included ensuring production that honored bioregional limits, buying agricultural products from local farmers (thereby supporting the local economy and reducing transport time and costs) and encouraging crop diversity (preserving soil health and aiding with pest management). Indeed, the vision of agriculture originally associated with organics was constructed on the view that farmers should be seen as the primary stewards of their land and the backbone of local and sustainable food systems. In addition, the organic farming movement was initially conceived as an alternative to the dominant corporatism, power relations and management practices of the existing food system. These goals, however, fell to the wayside in the decade between passage of the 1990 Organic Foods Production Act and the National Organic Standards developed to implement that statute and finalized in 2000. In the interest of finding a compromise between small and large growers, the final rule largely reflected minimum guidelines aimed at allowing farmers to remain competitive in international trade. Economic concerns superseded the sustainability and social justice aims of the original organic movement. As Guthman has observed,

A focus on allowable inputs has minimized the importance of agroecology, enforcement has become self-protective and uneven, and reliance on incentive-based regulation has created a set of rent-generating mechanisms that has profoundly shaped who can participate and on what terms (2004, p.111).

Nonetheless, despite this reality, one of the most common solutions posed today to “fix” the food system in the U.S. is for it to “go organic.” However, as Guthman’s argument and the statistics above suggest, even if all family farms were to be certified organic, that outcome would not necessarily produce a sustainable food system, especially if sustainability is defined as, per the Green New Deal, “ensuring universal access to healthy food” and “sustainable farming and land use practices that increase soil health” (H.R. Con. Res. 109, 2019, pp. 8-9). Given current market incentives to scale up operations (i.e., increase acreage and specialize) and ship food to the highest bidder, it is likely that merely encouraging organic production without paying attention to the income inequality currently evident in the agricultural sector will lead to further consolidation of farm operations. A still more centralized food system would require heavy government oversight to ensure it adequately distributed its production to all Americans and to ensure that system’s protection from potential bioterrorism and food-borne illnesses.

Small is Beautiful but Is It Sustainable?

It is debatable whether an agricultural sector rooted in small-to mid-scale farming (certified organic or not) would be more sustainable than a centralized, industrial one. In any case, today’s food system in the U.S. already operates largely on the basis of the latter model. However defined, large-scale farms account for 62.5% of fruit and vegetable production and 69.3% of dairy production (USDA 2019). On the positive side, these farms can supplement any gaps (particularly in terms of quantity) in regional food systems that local farmers either cannot or will not fill. Large farms often specialize by growing only one type of crop across several thousand acres, making them exceedingly efficient in comparison to smaller and often more diverse operations.

Is this sustainable? It depends on the analytic lens used to consider the question. In terms of agrobiodiversity, such a scenario is most certainly not sustainable. Monocropping (growing one crop on the same land every season) has been linked to decreased soil health, the destruction of native microorganisms and increased risk of pest and disease damage (Loviasa et al. 2017; Reddy 2017). Recalling the Green New Deal’s goal to invest in soil health, the prevalence of monocropping on large-scale farms speaks again to the need to differentiate between agricultural properties based on size and actual practices instead of certification.

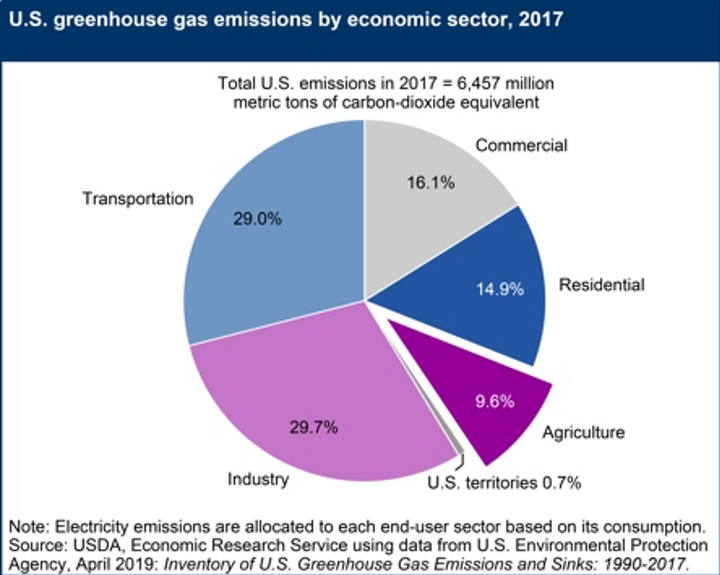

Another lens through which one can evaluate large-scale farms is by the level of greenhouse gas emissions they produce. As noted above, however, the transport-related “food miles” associated with most produce in the U.S. makes it difficult to argue that our current level of centralized production is sustainable. The net numbers, however, may not be as damning as this ratio suggests. The Environmental Protection Agency combines agriculture and forestry into a unified category, as land-based activities. When so considered, the agriculture and forestry sectors contribute approximately 9.6% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, while also providing “a net sink of 270 MMT CO2 eq. in 2013” (EPA 2019; USDA 2016). By “net zero” standards, therefore, the United States agriculture and forestry sector is effectively “carbon neutral” as is. In addition, and as Figure 2 suggests, it can be argued that agriculture and forestry are more sustainable than the other major sectors of the economy.

Nonetheless, if sustainability is to mean more than carbon neutrality and actually guide efforts to realize the transformative social justice goals of the Green New Deal and the organic farming movement, its proponents will need to harness the local eco-knowledge and know-how of farmers in the U.S. who are actively practicing regenerative, rather than degenerative, activities. Carbon neutrality obscures who is doing what and how; information that policymakers need to know if they are to enact provisions that will lead to climate justice in the longer term.

All of this said, while the desirability of a centralized food system is debatable, the power dynamics of the existing food system are not. The industry’s market imperatives and the political regulatory climate presently favor large-scale operations. If the past forty years of United States agricultural policy is taken for evidence, the nation can expect to continue scaling up the average size of the producing units of its agricultural sector and to rely on the owners of corporations to determine its definition of what constitutes “sustainable” agriculture.

Since former national Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz (1971-1976) told farmers in the 1970s to “get big or get out,” small and mid-sized property farmers have seen the writing on the wall. While many use regenerative practices such as planting cover crops, planning crop rotation and using no-till cycles on their land, they cannot afford simultaneously to obtain organic certification and compete with the large-scale farms now driving down the retail price of such products. In addition, many farmers already struggling to pay their bills are facing the prospect of costly operating upgrades imposed by the 2011 Food Safety and Modernization Act (i.e. time-intensive reporting requirements and creating near-sterile conditions in their fields and barns). Small acreage farmers grossing under $25,000 per year in revenues from their operations are exempt from many of these regulations, and that fact may explain why the number of such farms is rising. Most farms attaining this level of income are part-time or hobby farmers who report another primary occupation, a type of buffer against the increasing costs of farming. The real burden of these strictures falls on mid-scale full-time farms, the so called “disappearing middle,” symptomatic of the U.S.’s rising income inequality and its implications for who possesses the capacity to capitalize agricultural operations.

Given the cost squeeze many are now confronting, many mid-sized family farmers have given up their trade and sold their land. The American Farmland Trust estimates that 175 acres of farmland is lost to development every hour (2018). One can think of that acreage as a physical representation of the losers in the fight for control of the U.S. food system. Where small and mid-scale farming is no longer profitable, it is inevitable that more land will be sold to developers, stripped of its healthy microorganisms, and covered in impervious surfaces. Driveways and apartment building parking lots do not store carbon while cow pastures and cover crops do. This trend represents a definitive loss to communities losing local farms and to efforts to promote eco-friendly land use.

Concluding Thoughts

The Green New Deal is just one example of policymakers calling for agricultural sustainability without specifying at what scale such should occur and how and which farmers would be helped or hurt by attempts to realize such goals on the basis of existing production structures and land ownership conditions. This article has been primarily concerned with the common fallacy that assumes “family farmer” and “sustainability” are equivalent, a trap into which Green New Deal proponents appear also to have fallen. While corporations and industrial farming practices may be part of the problem, it must be noted that existing agricultural policy also supports their dominance of the food system.

Farmer-philosopher Wendell Berry wrote an insightful essay in 2012 entitled “Think Little,” in which he described the unique contributions that small farmers make to the environmental cause:

A good farmer who is dealing with the problem of soil erosion on an acre of ground has a sounder grasp of that problem and cares more about it and is probably doing more to solve it than any bureaucrat who is talking about it in general (2012, p.78).

It is important to pay attention to the nuances of who the farmers are in the U.S. today and to recognize that some of them meet Berry’s ideal of sustainable land stewardship and some fall hopelessly short of that vision.

Nonetheless, Berry’s sentiment was echoed in recent years by a report from the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development “Rio+20” summit, that argued that, “a small-scale farmer can be thought of as a nuclear unit for the environmental management of land and its biodiversity, an important source of cultural value and a fundamental pillar of national development” (2012, p.16). Development and competition with large-scale industrial farms are now displacing these stewards and replacing them with building projects and cul-de-sacs, leading to a diminished availability of healthy, locally produced foods for consumers. If the leaders behind the Green New Deal are serious about addressing systemic injustice while improving the health of our soils, it is imperative that they become much more aware of the scale and power dynamics of the current agricultural sector in the U.S. and craft future policies that take those realities into consideration.

References

American Farmland Trust. (2018). Farms Under Threat: The State of America’s Farmland. Retrieved from https://s30428.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/09/AFT_Farms_Under_Threat_May2018-maps-B_0.pdf

Berry, W. (2012). A Continuous Harmony. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint.

Berry, W. (1977). The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

EPA. (2019). Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2017. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-04/documents/us-ghg-inventory-2019-main-text.pdf

Green New Deal, No. 109 (2019). United States.

Guthman, J. (2004). Agrarian Dreams: The Paradox of Organic Farming in California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hagen, J.W., D. Minami, B. Mason, and W. Dunton. 1999. “California’s Produce Trucking Industry: Characteristics and Important Issues.” Center for Agricultural Business, California Agricultural Technol- ogy Institute, California State University – Fresno.

Lovaisa, N. C., Guerrero-Molina, M. F., Delaporte-Quintana, P. G., Alderete, M. D., Ragout, A. L., Salazar, S. M., & Pedraza, R. O. (2017). Strawberry monocropping: Impacts on fruit yield and soil microorganisms. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 17(4), 86–883. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-95162017000400003

Ocasio-Cortez, A., & Markey, E. Green New Deal (2019). House of Representatives. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hres109/BILLS-116hres109ih.pdf

Pirog, Richard S. and Benjamin, Andrew. (2003). "Checking the Food Odometer: Comparing Food Miles for Local versus Conventional Produce Sales to Iowa Institutions." Leopold Center Publications and Papers. 130.

Reddy P.P. (2017). “Intercropping.” In: Agro-ecological Approaches to Pest Management for Sustainable Agriculture. Springer, Singapore. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1007/978-981-10-4325-3_8

Sands, R. (2019). Climate Change. Retrieved February 6, 2020, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/natural-resources-environment/climate-change/

The Associated Press. (2018, March 6). General Mills To Create South Dakota’s Largest Organic Farm. CBS Minnesota. Retrieved from https://minnesota.cbslocal.com/2018/03/06/general-mills-organic-farm-south-dakota/

UNCSD. (2012). General Assembly Resolution 66/288 The Future We Want. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/733FutureWeWant.pdf

USDA. (2016). U.S. Agriculture and Forestry Greenhouse Gas Inventory: 1990–2013. Technical Bulletin, 1943.

USDA. (2019). America’s Diverse Family Farms. Retrieved from https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/95547/eib-214.pdf?v=9906.4

June Ann Jones is a student in the Alliance for Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought PhD program at Virginia Tech and a member of the Community Change Collaborative. She is also an instructor in political theory for the Department of Political Science at Virginia Tech and an adjunct instructor of philosophy at Harford Community College. Her research centers on environmental political theory and agrarian studies. Jones hails from Harford County, Maryland, where her family is engaged in full-time vegetable and Christmas tree farming.

Publication Date

February 13, 2020